|

The Future of Carolina Coliseum... Carolina Coliseum will remain USC owned and operated for atleast 1 more year. The NEW Coliseum is slated to be completed October 2002. What will happen to this coliseum after 1 year? Good question. Hopefully it will remain standing.

Columbia Inferno hockey team has signed a one year lease to remain in the Carolina Coliseum one more season with an option to remain a second season after that. Please visit our forums to read more about it.

Please visit our forum pages for updates on the new arena and it's progress as well as pictures.

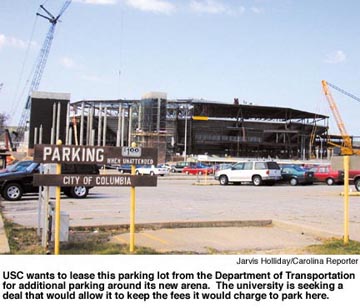

Below are some photos of the construction progress of the NEW arena. The ground breaking was at the end of April 2001.

|

|

| Progess of the new arena as of August 30, 2001 |

|

|

| New arena construction as of Jan. 20, 2002 |

|

| Arena construction progress mid-February 2002. |

Arena 'not just a USC building'

Manager says new facility will be used for variety of events

By JEFF WILKINSON

Tom Paquette is an entertainment junkie. "I love everything about putting on events," the Norristown, Pa., native said. "I get a rush from a full house. Everybody's having fun, and I'm a part of it." Paquette, 34, is the manager of USC's new 18,000-plus seat arena, which is being built on Lincoln Street in Columbia. He'll run the facility for the Philadelphia-based Global Spectrum management firm.

When the arena opens in November, Paquette plans to roll out about 140 events a year. The emphasis will be on the community; only about 25 percent of the dates will be Gamecock sports. "This isn't just a USC building," he said. "It represents a tremendous investment by the university, the counties and the city. "Events that benefit the community also benefit the building's bottom line. It makes sense to pull in every segment of the community we can. You don't build these buildings to go empty."

Look for ice shows, rodeos, professional wrestling, circuses, figure skating, and the ubiquitous tractor pulls and monster truck rallies. "We've got a lot of things in the pipeline," said Paquette, who moved to Columbia last year with his wife, Sarah, and children Mac, 5, and Hannah,

11 months.

Since November, Paquette has been settling into his new city and job after stints managing the 18,000-seat Kemper Arena in Kansas City and the 7,000-seat Tsongas Arena in Massachusetts. He most recently worked at the First Union Spectrum and Center in Philadelphia.

"We're not ready to announce the events yet -- we haven't even got a box office," Paquette said. "But we're going to have all the major family entertainment shows. And we think the arena is going to be a conduit to bring in many of the concerts that have been bypassing Columbia."

Also, in the future expect exhibition games featuring the NHL's Philadelphia Flyers and the NBA's Philadelphia 76ers. (The arena won't be open in time for this year's exhibition season.)

NATIONAL TIES

The two teams are owned by Global Spectrum's parent company,Comcast-Spectacor. Comcast also owns the First Union Spectrum and First Union Center, which are 18,000- and 21,000-seat arenas, respectively. The company also owns minor league baseball and hockey teams, and manages about 30 arenas, convention centers and stadiums across the nation and in Canada. Global Spectrum was hired by the university last year to manage the arena, the Carolina Coliseum and perhaps the Koger Center.

The company's management of the coliseum has been delayed by negotiations over a lease for the Columbia Inferno hockey team. University officials haven't decided if the firm will manage the Koger Center. Paquette said that he believes having the Inferno play in the older existing

coliseum would be a good fit.

"Clearly they can get a better rental agreement in the coliseum," he said. "It gives the university a tenant for that building. And it gives everybody more flexibility in scheduling."

Paquette has a lot of experience balancing the needs of a university with those of the community. He served for six years as assistant manager of Thompson-Boling Arena in Knoxville, home to the SEC's Tennessee Volunteers.

MAJOR CONCERTS

The company's management of other facilities and its relationships with band managers and booking agents will make attracting shows and concerts easier, Global Spectrum vice president Ike Richman said. "We know the producers, the promoters and presenters," he said. "And we have a proven track record." The company has close ties with Clear Channel Entertainment, one of the world's largest promoters of live entertainment. Clear Channel also owns scores of radio stations -- six in Columbia -- and entertainment venues such as Verizon Wireless Amphitheater in Charlotte.

Paquette noted that Wilson Howard, who books the east coast from Washington, D.C., to Florida for Clear Channel, is a Columbia resident. Howard, one of the most respected booking agents in the Southeast, called Global Spectrum "an excellent company." "They manage some of the top buildings in the country," he said. "Their record speaks for itself."

Howard also backed up the company's and university's claim that the arena will pull in the nation's top acts. "It will put us into the ballpark to get the triple-A shows," he said. "It's going to be great for the city." Howard said that shows began bypassing Columbia when large arenas in

Charlotte, Greenville and other cities in the region were built. They dwarfed the Carolina Coliseum and were more profitable for promoters. The new arena will turn that around, he said. "And I live seven minutes from there," Howard said, laughing. "So the routing (travel time) for me is great."

Paquette downplayed fears that the acoustics in the building were designed more for roaring basketball crowds than live music. For one, he said, the fabric seats throughout the building will soak up sound, in contrast to the bleachers used in some buildings. And sound systems used by touring bands also have improved, allowing stage crews to "shape" the sound to the building.

Arena architect Larry Ray said that the building's design, which places as many people as close to center court as possible, will help with the acoustics. "What's best for both conditions (music and noisy basketball fans) is to get the crowd close," he said. NEWS OF INTEREST TO THE CHANGEOVER CREW:

| Changeover photo taken February 7, 2002 |

|

|

COLISEUM: From page 2A of THE STATE newspaper February 14, 2002 edition:

CORRECTIONS AND CLARIFICATIONS:

"The stage manager for the Carolina Coliseum's changeovers from basketball to ice hockey was misidentified in Tuesday's sports section. The stage manager is Nancy Hanko. Also the name of the coliseum worker Jeff Numberger was misspelled."

From hardwood to hockey By BOB GILLESPIE Senior Writer

At 9 p.m. Thursday, the South Carolina women's basketball

team puts the final touches on a 64-59 win over SEC rival

Georgia. Players retreat to locker rooms, coaches discuss the game with reporters, and 4,111 fans head for the Carolina Coliseum exits.Already, the clock is counting down on a different sort of game.

At 9:30 a.m. Friday, the Columbia Inferno is scheduled to take home ice for practice, in preparation for that night's game against the Florida Everblades. Before that can happen, Coliseum and Inferno workers must convert the Frank McGuire Arena court into the Inferno's ECHL rink.

The process has been done so many times this season -- hoops to hockey, hockey to hoops -- that changeover supervisor Jeff Numberberger's crew of 15-25 workers can do in 10 hours or less what used to require 14. "They've got it all choreographed by now," says the Inferno's Steve Smart, who will put the finishing touches on the job early Friday. But at the moment, that's still 12 hours and a total makeover (cost: $8,400 per) away.

9 P.M.

Even as spectators leave, maintenance workers remove team seating, scorer's table, press row and chairs. Next, they push the retractable bleachers back into storage areas flush with the floor-level walls. The process takes about two hours. Here we see the first concessions to a year-round sheet of ice. Adding a rink to the Coliseum meant elevating the bleachers by six inches. So

specially built steel platforms and runners were constructed by Columbia's Chao and Associates, Inc., which allow the bleachers to slide into place. With the bleachers retracted, the 200-pound, ¼-inch steel runners are removed and put in storage.

11 P.M.

Numberberger's staff wheels out 14 carts used to remove the hardwood floor. The court consists of the equivalent of 196 four-foot-by-eight-foot sections, which weigh 175 pounds each and fit together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. The arrangement is 14 rows of 14 pieces each; every other row has 4x4 pieces at each end so that when the floor is laid down, the seams overlap. To disassemble the puzzle, plates that hold end pieces in place are removed. Three workers slide each piece out, then lift it onto the specially

constructed carts, which roll on balloon tires so as not to damage the ice underneath.

The carts, each carrying 14 pieces of floor, about 2,700 pounds total, are then pushed by workers to the entrance of the Elephant Room, where a forklift hoists and then carries them to storage. The process begins with the court's end zones and works toward center court. "With new people working, a row probably takes 10 minutes," Numberberger says. Veterans take less time.

1 A.M.

Next, workers pick up 4x8 sheets of homosote, 1-inch thick sections of recycled newspaper which weigh 10-12 pounds each and insulate the floor from the ice. These, too, are stacked on carts and rolled off the ice. Some pieces are cut into rounded shapes to fit into the curved corners of the ice rink. A new homosote cover for a hockey rink costs about $25,000; the Inferno bought this one used for $10,000. "If we were only going to be here two years, it just made sense," Smart says.

1:30 A.M.

Now come the components that turn a sheet of ice into a hockey rink: dasher boards and plexiglass, steel uprights that fit into holes in the floor on the outside of the six-inch-high rink wall, and ¼-inch aircraft cable, which holds the entire setup in place. Also brought out are materials for building the eight wooden boxes on each

side of the rink used for the announcer's booth, penalty boxes, and home and visitors' team boxes. After hauling out all the stuff, the crew takes a well-deserved half-hour dinner break.

3:30 A.M.

Imagine a giant Erector set, and you've got an idea what's next. Dasher wall sections sit atop the rink wall, held in outside and kick plates on the ice side. Plexiglass sheets sit atop the wall sections in a O-inch groove. The cable is threaded through hooks on the uprights, and the cable is tightened with turnbuckles, the way the Highway Department does median cables on I-77.

Once the wall reaches from the Zamboni gate to center ice, workers put together the iceside boxes. Carpeting is put down in the rink's four corners for VIP suites (three per corner), and workers set up chairs and tables. "Usually, by 8-9 a.m., everything surrounding the ice is complete,"

Numberberger says. By that time, Smart is already doing his thing.

7 A.M.

The Inferno's homosote cover leaves the ice surface something less than pristine. Smart fires up the Zamboni, which, in fact, isn't a "Zamboni" at all, but an Olympia: a less costly machine that does the same thing. Smart takes 10-12 trips (about 90 minutes worth, at a maximum 17 mph)

across the ice, scraping it with the Olympia's 80-inch blade set at a 10-degree angle and scooping off about 1/16th of an inch of ice, which is funneled into the machine's ice bin (and later dumped in a parking lot). Once all the dirty ice and loose snow are gone, Smart does a final circuit, the Olympia dumping hot water onto the surface and wiping it smooth with a terrycloth rag.

In 8-10 minutes the water freezes, leaving a new, fast surface for hockey. The goals are installed and at 9:30 a.m., the Inferno players are skating across the same space where the Gamecocks ran their fast breaks. There the ice stays -- until the next USC game, when it's done all over

again. This time, in reverse.

|